David J. Kupstas, FSA, EA, MSEA Chief Actuary

With the new year having just begun, our retirement plan clients are busily working on compiling the information we need to do their year-end calculations. One of the most critical pieces of data we need is compensation paid to each employee for the year just ended. Without that number, we would not be able to calculate the match or other employer contributions, determine whether the ADP or ACP nondiscrimination tests were satisfied, or determine who the Highly Compensated Employees will be.

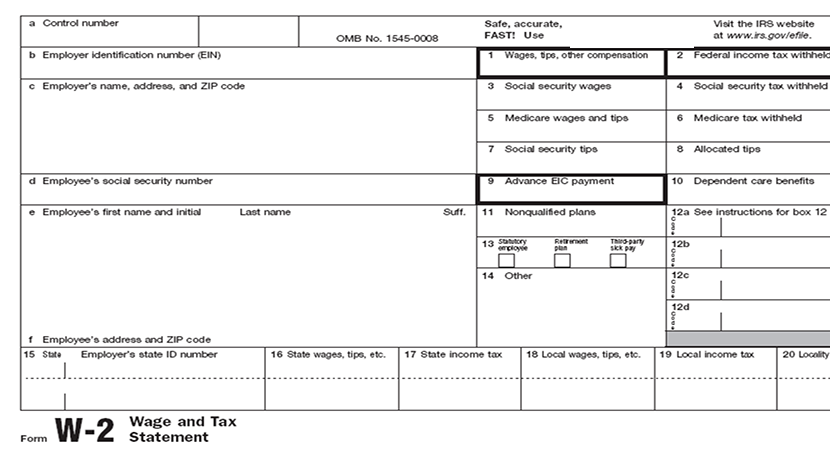

Inevitably, some of our clients will ask, “Where do I find the compensation number to report to you?” This is definitely a valid question – and one that should probably be asked at least once by every plan sponsor. Usually, there is not a single number that can be plucked off the payroll report or Form W-2 and reported to us. While there may be an easy starting point like W-2 pay, there are usually some additions and subtractions before plan compensation takes shape.

Plan Document Is Where to Find Comp Definition

A plan document will have a base definition of compensation. Maybe compensation will be defined as “Wages, tips and other compensation on Form W-2,” “Code §3401(a) wages (wages for withholding purposes)”, or “415 safe harbor compensation.” Unless there is a specific reason known in advance why one of these definitions should be chosen over the others, any of them will be fine. Our clients often choose W-2 pay, although even that can be tricky because where on the W-2 is your starting point? Box 1? Box 3? Box 5? Hmmmm.

Once the base definition has been selected, the plan sponsor must make a decision about whether to include or exclude in its definition of compensation items such as the following:

- Salary reductions, such as 401(k), 403(b), and 125.

- Reimbursements, expense allowances, and fringe benefits.

- Compensation paid prior to a participant’s entry into the plan.

- Military Differential Pay.

- Overtime.

- Bonuses.

- Commissions.

For example, Tim from the client’s payroll office knows that plan compensation is the sum of salary, back pay, bonus, auto allowance, and group term life insurance. All of these items are reported in Box 5 of Form W-2. All of the items are listed on Tim’s payroll report under Gross Pay except for group term life insurance, which is listed as an Employer Tax or Contribution. Another company’s plan might have the same definition of compensation as Tim’s, but the numbers might be found in a different place on the payroll report if that company uses a different payroll service. If a plan excluded any of these items from its definition of compensation, those items would have to be subtracted out. In that case, even though the plan’s base definition of compensation is W-2 pay, the plan compensation figure would not actually be found on the W-2.

In our experience, it is rare to exclude 401(k) deferrals from plan compensation, but we do see it from time to time. Suppose an employee makes $50,000, defers $5,000 into the 401(k), and is to receive a 10% profit sharing contribution. Normally, the profit sharing contribution would be $5,000, but it would be $4,500 if salary deferrals were excluded from plan compensation. The employee would in effect be penalized for contributing to his 401(k) account.

It is common to exclude compensation paid prior to a participant’s entry into the plan. If an employee is eligible for the plan on July 1, why should he receive any benefits based on pay earned before entering the plan? If the employer makes this choice, however, it must be careful. Whoever is reporting the compensation has to remember to separate out the pre-participation pay for new entrants and report just the pay while in the plan. Also, any minimum contributions required because the plan is top-heavy must be based on full-year pay, meaning the decision to exclude pay prior to plan entry could be moot.

There are no one-size-fits-all instructions we can give with respect to reporting plan compensation. There are so many compensation definitions a plan can choose from and so many ways pay is tracked and categorized by companies. Instead, it would behoove every plan sponsor to sit down with its consultant and go through item by item what should be reported as plan compensation.

Regulatory Definitions of Compensation Keep Plan Sponsors Honest

Many of our clients wish to maximize plan benefits for owners and other selected employees while minimizing benefits to all other employees. It would be tempting to define compensation in such a way that most or all of the benefits flowed to these selected employees. An extreme example might be to exclude an individual’s first $150,000 of compensation from the plan’s definition. That’s one way to ensure that owners and top-paid employees get most of the benefits. Such a definition would not fly for a number of reasons, but there are more subtle ways of steering benefits toward the higher-paid. Excluding overtime pay is one way to do it, since it is likely lower-paid employees will be the ones to receive overtime pay.

Sections 414(s) and 415(c) of the Internal Revenue Code and the regulations thereunder have rules about the definitions of compensation. Among the rules are that a plan’s definition (i) must not by design favor Highly Compensated Employees, (ii) must be reasonable, and (iii) must not be discriminatory in favor of HCEs. There is a nondiscrimination test for compensation under which the plan’s definition is compared to a standard definition for all HCEs and Non-Highly Compensated Employees. The ratio of plan compensation to the standard definition must not be significantly lower for NHCEs than it is for HCEs. Alternatively, the plan can run a general nondiscrimination test, such as cross-testing, using a standard definition of compensation.

We have a client that defines plan compensation in its profit sharing plan as base pay. Overtime and bonuses are excluded. We have tested this definition over the years using both the compensation test and the general nondiscrimination test. It has always worked out just fine. While the lower-paid employees are not receiving contributions on their overtime pay, the higher-paid employees are paid large bonuses for which they do not receive profit sharing contributions. Since this definition of compensation puts HCEs at a disadvantage, it is acceptable.