David J. Kupstas, FSA, EA, MSEA Chief Actuary

This is Part 1 in a two-part series on the mechanics of cross-testing.

What is an EBAR? It sounds like a place where you can order a cold, refreshing drink while surfing the Web. In the retirement plan world, it stands for Equivalent Benefit Accrual Rate and is a fundamental part of using cross-testing to ensure that a plan meets the nondiscrimination rules.

Rules Ensure Lower-Paid Employees Share in Plan Benefits

In society, there are rules about discriminating on the basis of race, religion, and other characteristics. Qualified retirement plans have rules on discriminating based on one’s status as a Highly Compensated Employee (HCE) or Non-Highly Compensated Employee (NHCE). Internal Revenue Code Section 401(a)(4) says a retirement plan does not qualify for tax-favored treatment if contributions and benefits discriminate in favor of HCEs. The Code subsection itself takes up a modest two sentences. The regulations explaining what discrimination means go on for 80 pages.

Given a preference, most small businesses would rather give more retirement contributions and benefits to HCEs. Business owners are automatically considered HCEs regardless of their pay. Owners usually like receiving most of the benefits in a retirement plan. If they had to give most of the benefits to their employees, then they are better off financially not having the plan and just taking the money as bonus and paying taxes on it. There is often a desire to reward non-owner HCEs with bigger benefits, as well. These may be executives or longtime employees who are vital to the success of the business. The nondiscrimination rules are in place to ensure that NHCEs don't get left out of the benefit party.

Under the nondiscrimination rules, some contribution and benefit structures that look discriminatory may not be, while some structures that do not appear to be discriminatory actually do not satisfy the tests. Let’s look at a couple of examples.

Discrimination or Not? You Be the Judge

Louise has a salary of $150,000 and is an HCE. Beth earns $50,000 and is a NHCE. Their employer gives both of them a $1,000 contribution in the company profit sharing plan. Because Louise and Beth are receiving the same dollar contribution, this is not discriminatory under Section 401(a)(4). Suppose the employer instead gives each of them a profit sharing contribution of five percent of pay. This is $7,500 for Louise and $2,500 for Beth. Although Louise’s contribution is a lot more dollars than Beth’s, this allocation is not discriminatory because both are receiving the same percentage of their salary.

Now let’s add a few wrinkles. Let us say that Louise is 60 years old and Beth is 30 years old. The employer decides to give Louise a $30,000 profit sharing contribution (20% of pay), while Beth receives $2,500 (5% of pay). Many people would look at those numbers and conclude that this allocation is discriminatory and therefore does not pass Section 401(a)(4). Louise (the HCE) is getting 12 times the dollars Beth (the NHCE) is. Even if you look at percentages of pay, Louise’s is four times what Beth’s is. This surely must be discriminatory and not legal, right?

Well, no, it’s not. We wouldn’t go through all the trouble of concocting an example that didn’t pass, would we? By using cross-testing, the above allocation of contributions to Louise and Beth can be shown to be not discriminatory under the regulations.

If Contributions Testing Doesn’t Work, Look at Benefits Testing

There are two ways to show nondiscrimination. Either the current contributions can be tested, like in the example where both employees receive the same dollar amount or same percentage of pay, or the benefits payable at retirement can be tested. A plan needs to be nondiscriminatory on one basis or the other, not both. Since the allocations to Louise and Beth seem to be discriminatory on a contributions basis, we should look at them on a benefits basis. That is, if Louise’s $30,000 and Beth’s $2,500 were put into an account earning interest, would the amounts they could withdraw at retirement be discriminatory in favor of Louise?

To test these allocations on a benefits basis, we need to convert the contributions to future retirement benefits, hence the term “cross-testing.” This is where the EBAR comes in. EBAR is the monthly retirement benefit that the current contribution could theoretically buy at some future age, usually age 65.

EBAR Math

The steps in determining the EBAR are as follows:

- Accumulate the current contributions to age 65 using a standard interest rate in the regulations. The regulations allow any interest rate between 7.50% and 8.50%. Although these rates seem high nowadays, the regulations were written in the early 1990s when these rates were in fact more standard. We normally choose 8.50%. Louise’s current $30,000 would grow in five years at 8.50% to $45,109.70 [$30,000 × (1.085)5 = $45,109.70]

- Divide the accumulated contribution amount by the annuity purchase rate. The annuity purchase rate is an actuarial present value. It is the price one would have to pay to purchase a monthly annuity of $1 per month for life using an interest rate and mortality table assumption. The regulations have a number of standard mortality tables to choose from. Using the 1983 IAM mortality table and 8.50% interest, the annuity purchase rate at age 65 is $105.9347. Therefore, the result for Louise under this step is $45,109.70 ÷ $105.9347 = $425.83.

- Multiply the result in (2) by 12 to convert from a monthly annuity to an annual annuity. For Louise, this is $425.83 × 12 = $5,109.96.

- Divide this future annual annuity amount by current compensation. For Louise, this is $5,109.96 ÷ $150,000 = 3.41%. This is her EBAR.

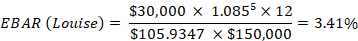

To reiterate in words, a contribution of $30,000 made to 60-year-old Louise today could theoretically buy a benefit at age 65 of 3.41% of her current compensation. Mathematically, this may be shown as

The EBAR for Beth is

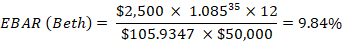

The EBAR for Beth is

Discrimination Against HCEs is Fine

Discrimination Against HCEs is Fine

Beth’s EBAR is roughly three times Louise’s. What does all this mean? It means that even though Louise is getting a much larger current profit sharing contribution, compared either on a dollar basis or a percent-of-pay basis, Beth’s contribution theoretically will grow into a much bigger benefit at retirement as a percent of current pay. This is because she has 35 years until projected retirement for her money to grow, while Louise’s profit sharing account has only five years to grow. This is an example of the magic of compound interest.

We know it is a problem if benefits discriminate in favor of Louise. Do we now have a problem since Beth’s EBAR is so much larger than Louise’s? No. The rules allow discrimination against HCEs as much as the employer would like. It is discrimination in favor of HCEs that Section 401(a)(4) is designed to prevent.

In our next installment, we will do an extended example with additional employees and including a 401(k) feature along with the profit sharing contribution.